|

|

Defending Louisiane Against Union Invasion: |

|

|

Contents

1) South Louisiane Battles with the Union Army2) Battles fought in the South Louisiane Acadian Region

3) South Louisiane Battlefields - Page 1

4) South Louisiane Battlefields - Page 2

South Louisiana (Acadiana) Civil War Battlefields

(on this page)

Click to jump to specific battle

- Note that the battles are seperated into three different pages.

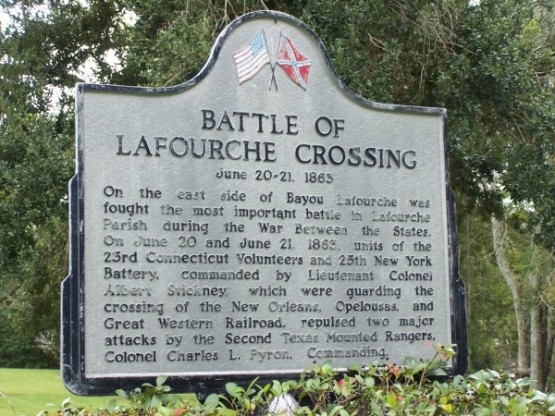

12) June 20-21, 1863 - Battle of LaFourche Crossing

13) July 23, 1863 - Battle of Brashear (Morgan) City - (Fort Star)

14) May 21-July 9, 1863 - Battle of Donaldsonville (Fort Butler)

15) July 12-13, 1863 - Skirmish at Kock's Plantation / Cox's Plantation

16) May 16, 1864 - Battle of Mansura / Smith's Place / Marksville

17) May 18, 1864 - Battle of Yellow Bayou / Norwood's Plantation

Go to South Louisiane Civil War Battlefields - Page 1

Go to South Louisiane Civil War Battlefields - Page 2

Battles fought in the South Louisiane Acadian Region

- (Page 3 - Continued)

|

Note: Click on Each Battle to open it's description entry on "Wikipedia"

12) June 20-21, 1863 - Battle of LaFourche Crossing (Thibodaux / Raceland, Bayou Lafourche, LA)

|

From Wikipedia: Confederate Major General Richard Taylor sent an expedition under Colonel James P. Major to break Union supply lines, disrupt military activities and force an enemy withdrawal from Brashear City and Port Hudson. Major set out from Washington, Louisiana, on Bayou Teche, heading south and east. While marching, his men conducted raids on Union forces, boats and plantations and in the process recaptured liberated slaves and captured animals and supplies. Brigadier General William H. Emory, commanding the defenses of New Orleans, assigned Lieutenant Colonel Albert Stickney to command in Brashear City and to stem the Confederate raid if possible. Emory informed Stickney of Major’s descent on LaFourche Crossing and ordered him to send troops. Feeling that no threat to Brashear City existed, Stickney, himself, led troops off to LaFourche Crossing, arriving on the morning of June 20. That afternoon, Stickney's scouts reported that the enemy was advancing rapidly. Confederate forces began driving in Stickney’s pickets around 5:00 p.m.. Southern cavalry then advanced, but was driven back. After Union troops fired a few rounds, the Confederates withdrew in the direction of Thibodeaux. In the late afternoon of June 21, the Confederates engaged the Union pickets, and fighting continued for more than an hour before the Rebels retired. At about 6:30 p.m., the Confederates reappeared in force, started an artillery duel, and charged the Union lines at 7:00 p.m. An hour later, the Confederates disengaged and retired toward Thibodeaux. The Union held the field. Despite the defeat, Major’s raiders continued on to Brashear City. |

|

Official Records on the Battle of Lafourche Crossing from U.S. War Dept. - The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Page(s) 192 - 201 W. FLA., S. ALA., S. MISS., LA., TEX., N. MEX. Chapter XXXVIII. OPERATIONS IN LA., WEST OF THE MISSISSIPPI. |

|

Author: United States. War Dept.

Numbers 3. Report of Lieutenant Colonel Albert Stickney, Forty-seventh Massachusetts Infantry, of engagement at La Fourche Crossing.

COLONEL: I have the honor to report that, in accordance with Special Orders, Numbers 16, from your headquarters, I proceeded to Brashear City on June 7 last, and assumed command of the forces there. I found things in a very disorganized condition, and immediately proceeded to put the place in the best state for defense that I could, and to obtain all possible intelligence of the force and designs of the enemy in that vicinity. I reported to you from time to time the operations at that post, and at the same time made what preparations were in my power for defending any other threatened points on the line of the Opelousas Railroad. On the morning of June, at about 4 o'clock, I received a telegram from you, informing me that the enemy were advancing in force on La Fourche Crossing, and ordering me to send re-enforcements to that point. Judging that there was no danger of any attack at Brashear City, of a day or two, at least, and thinking that affairs at LaFourche required my presence there, I left Major Anthony, Second Rhode Island Cavalry, in command of Brashear City, and went to La Fourche Crossing immediately, with such forces as I could spare from Brasher, intending to return as soon as possible to my former station. I reached La Fourche about 6 a. m., with 75 men of the Twenty-third Connecticut Volunteers and 115 men of the One hundred and seventy-sixth New York Regiments, 46 men of the Forty second Massachusetts, and two pieces of artillery, one 6-pounder gun and one 12-pounder howitzer. I had ordered Captain Blober, with his company of First Louisiana Cavalry, on the day previous to scout the country as far certainly as Nepoleonville, and farther, if possible with safety, and to send immediately any intelligence of the enemy he might obtain. He went only a mile or two beyond Labadieville, and returned with no intelligence whatever of any force on the Bayou La Fourche. He also reported that gentlemen from Napleonvile gave no information of any force in that direction. After my arrival at La Fourche, I sent out Captain Blober and his command again to scout the country above Thibodeaux. They returned on the afternoon of the 29th, reporting that they had been closely pursued by the enemy, and had lost 2 of their men. The force of the enemy advanced very rapidly on Thibodeaux that day, being almost entirely composed of mounted men and artillery, and captured nearly all the infantry stationed there and in the vicinity on the plantations, amounting to about 100 men. They were 47 men of the Twelfth Maine, with 2 Lieutenants, convalescents, from Brashera; about 10 men of Company D, One hundred and seventy-sixth New York Regiment, and a very few men who had been stationed as guards on plantations. Captain Blober's company was mostly composed of new recruits, and, in consequence, undrilled and undisciplined. Had their scouting been properly done, there was no necessity whatever of the infantry force at Thibodeaux being captured. They had only to retreat this side of the bridge over Bayou La Fourche, and then march down under cover of the levee. The enemy rested two or three hours in Thibodeaux before the bridge could have defended themselves against merely their advance guard. On the afternoon of Saturday, I received an order to send back two companies to Brashear, but, as the enemy were then advancing down the bayou to the crossing, I did not dare at that moment to weaken my force by sending them away. I sent a train back to Terre Bone to bring down to La Fourche the company and one piece of artillery there stationed. The enemy succeeded in capturing 1 commissioned officer of the company at TerreBonne, the others of the company escaping on the train and arriving safely at La Fourche. Immediately afterward the railroad and telegraph were cut at Terre Bonne, and the place occupied by cavalry. About 5 o'clock in the afternoon my pickets were driven in, and the cavalry of the enemy immediately afterward appeared in our front. I do not know how large their force was at that time, but judge it to have been under 100. Our position was as follows: The levee of the Bayou La Fourche is about 12 feet high; the railroad crosses the bayou over the top of the levee, nearly in a direction perpendicular to that of the bayou, and is about 12 feet above the level of the surrounding country. For 5 or 6 miles to the east of La Fourche Crossing a carriage road runs up and down the bayou on both sides, close to the levee, passing under the railroad on both sides of the bayou. We were on the east side of the bayou and north of the railroad, our front being parallel with the railroad, extending about 150 yards from the levee, and being about 200 yards from the railroad. From the right of our front, I had a line of defense running perpendicular to and resting upon the railroad. I was obliged to have my front farther from the railroad than it otherwise would have been, on account of trees sending which could not be cut down. The country around was level, affording full play for the artillery, and was covered with tall grass, which I subsequently had cut down, as it concealed, in a measure, movements in our front. A short time before our pickets were driven in, I had ordered a detachment of about 50 men, of the Twenty-third Connecticut Volunteers, under command of Major Miller, to lie down in the tall grass on both sides of the road long the levee, abut 450 yards in advance of our main line. After the first fire of the enemy, I found Major Miller some distance to the rear of his command, crouching in the high weeds on the levee. I ordered him under arrest, and ut in command of this detachment the next senior officer, who faithfully executed my order. The remainder of the infantry was drawn up in line along our front and the extreme left of our right flank, with the exsection of a company of convalescents, under Captain Fletcher, Twenty-sixth Maine, who were at the railroad bridge. Captain Blober's cavalry was posted so as to guard against the turning of our right flank. The artillery was posted as follows: 12-pounder gun on the railroad, at the point where it crosses the left bank of the bayou; two 12-pounder howitzers and one 6-pounder gun on our front, on the howitzers being placed on the extreme right, so that its fire could be directed to the front or right flank. After the cavalry of the enemy drove in our pickets, they continued to advance until fired upon by the detachment of the Twenty-third Connecticut Volunteers. A few volleys were exchanged without loss on our side, when our men fell back, and took position on the right flank. As the enemy were now in easy range, we opened upon them with shell and solid shot, the 12-pounder gun on the bridge doing the most execution. They stopped, seemingly surprised to find such preparations for their reception, and in a few that were killed or wounded by our fire. Soon after the disappearance of the enemy, I sent a flag of truce to obtain permission to move our hospital stores and sick from the hospital, which was in front of our hospital stores and sick from the hospital, truce went 2 1/2 miles toward Thibodeaux before meeting the pickets of the enemy, who refused to comply with my request. I, however, succeeded in moving safely all the contents of the hospital to our rear, and just after dark burned the building, lest it should interfere with the effectiveness of our fire, and that, at the same time, the light might enable me to perceive the movements of the enemy. For the same reason I had building fired on the other side of the bayou, anticipating that the Confederate might come down on that side and attempt to cross the railroad bridge. Up to this time, Saturday evening, June 20, our forces amounted to about 502 men, as follows: 195 of the Twenty-third Connecticut; 154 of the One hundred and seventy-sixth New York; 46 of the Forty-second Massachusetts; 37 of the Twenty-sixth Maine; 50 men in Captain Blober's cavalry, and about 20 artillerists, mostly of the Twenty-first Indiana. The men were kept under arms, at their several posts, ready to repel an attack at any moment. Pickets were thrown out on the front to a distance of about 400 yards, and squads of cavalry scouted on our right and rear. About 11 p. m. of the 20th, Lieutenant-Colonel Sawtell, of the Twenty-sixth Massachusetts, arrived with five companies (306 men). As he was the senior officers, I offered him the command, which he refused. I then ordered his regiment into line on the front, to relieve the men posted there. During that night no demonstration were made by the enemy. On the following morning, Captain Grow, of the Twenty-fifth New York Battery, reached La Fourche Crossing, with one section of his battery, about 30 men, one gun of which I ordered into possession on the extreme left of our front on the Bayou road, and the other within our lines, so that it could be moved to our front or right flank as occasion should require. We had begun throwing up slight earthworks, but they were at no point over 2 feet in height, and extended only a few yards in either direction from the angle formed by our two fronts. At different times during the morning reconnoitering cavalry of the enemy appeared in or front and at some distance on the right, but only came within fire of our outposts. A little after noon, a heavy rain commenced and continued until about 6.30 p. m., thoroughly drenching the men, who were in line a greater part of the time. This was necessary, as I could not depend upon their falling into position with sufficient alacrity at the least warning. About 4 p. m. the infantry and cavalry of the enemy, about 150 strong, engaged our outposts and pickets, but made no attempt to advance on our main force. An intermittent fire was kept up for an hour and a half, when the enemy retired, and our pickets again resumed their places. At 6.30 p. m. the Confederates again came in view, and this time in large force. Our position was much the same as on the previous night, except that two companies of the Twenty-sixth Massachusetts were on our front, two on our right flank, and the remaining one protecting the field piece on the bridge. The artillery was all posted as before described. The enemy advanced rapidly, and soon compelled the pickets to fall back on the main line, which they reached in rather a straggling condition at our left wing. Just about dusk the enemy opened upon us with one field piece (which appeared to be a 12-pounder howitzer), throwing shell and solid shot, when I ordered the reserve piece of the Twenty-fifth New York Battery to take such a position on the right as would enable them to reply to this piece. The howitzer of the enemy soon ceased firing, whether compelled by the shots of our piece or the bad quality of their ammunition I am unable to say. Prisoners subsequently stated that they had other guns in position, which the rain prevented their using. All this time our artillery had been constantly firing, using shell for the most part; but the infantry did not, as yet, reply to the straggling bullets which came from the enemy. The moisture of the atmosphere held the smoke of the cannon so close to the ground that it was almost impossible to ascertain the distance or numbers of the enemy, or on what point he would mass his force. At about 7 p. m. their loud shouts indicated that they were charging in our front. I immediately ordered the infantry to fire by rank and the artillery to use canister. Having no canister for the 6-pounder gun, we used in it packages of musket ammunition. Notwithstanding a most rapid but accurate fire on our part, the enemy, who had dismounted before charging, advanced boldly up to our lines, firing continually as they came. Our infantry became nervous, and no longer fired by rank, but at will. At the same time a strong attempt was made to turn our right flank. This was prevented (though at one time they seemed on the point of success) by the enfilading fire of our reserve piece and the speedily rally of the men there posted. The attack of the enemy was principally directed against our guns, and the cannoneers of two pieces became panic-stricken and fled. These were the guns of the Twenty-fifth New York Battery, and the Bayou road, and the 12-pounder howitzer at the angle of our front and right flank. The contest over these pieces was hand-to-hand. The enemy were driven off at the point of the bayonet. At length, at about 8 p. m., the Confederates, growing weary of a fight so unequal in its results, hastily retreated toward Thibodeaux, leaving a great number of their dead and wounded near our lines. Our actual force during the fight amounted to 838 men, of whom only ably 600 were engaged, the remainder being posted as a guard to the field piece on the bridge and to protect our right. This was necessary, because the darkness rendered it impossible to see the enemy's movements, and few of the troops were steady enough to trust them to make any rapid movement in the excitement of action. The actual force of the enemy engaged in the charge on our lines I estimated at about 600 men.

Our loss was as follows:

The enemy were engaged during the night in carrying away their killed and wounded who were outside of our lines, and the following morning 53 of their dead were counted inside of our pickets. When we entered Thibodeaux, Tuesday morning, nearly 60 wounded were found in the hospitals, from which I conclude that their loss in killed and wounded must have been 300, taking 50 as the number of their killed, and reckoning the ratio of killed to wounded as 1 to 4. The men who charged upon our lines belonged mostly to the Second Texas Mounted Rangers, Colonel [Charles L.] Pyron, claimed to be the oldest regiment in the Confederate service, and the they had never before been beaten in action. Their wounded in our hands thought that our troops must be Regulars, so steadily did they stand at their posts. But I regret to say that the train in waiting on the track left at the commencement of the fight without orders, carrying away some cowardly soldiers, and that during the battle some few left their ranks and sought shelter near and behind the railroad. Had the enemy brought up his reserve, which was in line at no great distance, at the time the cannoneers deserted their guns, or had he made his attack on the right flank with equal force and with the same persisted energy as was displayed upon our front, perhaps the result might have been different, although our troops, for the most part, stood manfully under so close a fire. Our men remained in line under arms the whole night, but there was no further attack. The next morning a flag of truce came in, requesting permission to bury their dead and carry away their wounded. This was granted, on condition that all the wounded men outside the camp lines should be paroled; that none of their drivers should come within our outposts, and that all wounded should be retained who were within our camp. As they agreed to these conditions, our drivers were engaged with the ambulances of the enemy during the morning in carrying to Thibodeaux the dead and wounded. About 11 a. m. Colonel Cahill arrived with the Ninth Connecticut Volunteers, a detachment of the Twenty sixth Massachusetts, and the other section of the New York Battery, and took command of the forces at La Fourche. Major Morgan, commanding the One hundred and seventy-sixth New York Regiment, through the action encouraged his men, and to him is due, in a great degree, the fine conduct that they showed. Captain Jenkins, commanding the Twenty-third Connecticut, displayed the greatest bravery and coolness. A Confederate officer seized him by the throat, demanding a surrender. The assault was immediately returned in precisely the same manner, when one of Captain Jenkins men bayoneted the Confederate. Lieutenant Starr, of the Twenty-third Connecticut, was the only commissioned officer injured in the action. He as wounded in the high, and afterward died in consequence of amputation and ensuing weakness. I desire particularly to mention Sergt. John Allyn, Company A, Forty-seventh Massachusetts Regiment, who has been with me since I was ordered to Brashear City, and has at all times rendered the most valuable service, going on dangerous scouts, once inside the enemy's lines, and showing at all times the greatest courage and remarkably sound judgment. His thorough knowledge of the country and habit of reporting facts only were of the greatest assistance to me.

Very respectfully, Page(s) 196 - 201 W. FLA., S. ALA., S. MISS., LA., TEX., N. MEX. Chapter XXXVIII. OPERATIONS IN LA., WEST OF THE MISSISSIPPI. Numbers 4 Report of Captain John A. Grow, Twenty-fifth New York Battery, of operations June 20-25, including engagement at La Fourche Crossing. METARIE RACE COURSE, July 5, 1863. SIR: An indisposition has prevented me from sending you an account of the movements of my battery since the 20th ultimo at an earlier period; but trussing even at this late day that it may not be without interest to you, I send you the inclosed statement. There may be much in it which you may desire to remedy. On the 20th day of June I received orders to proceed at once to La Fourche Crossing. The order having been received at about 4 p.m ., my battery, with all the baggage, was taken across the river and put on board the cars by 1 a. m. (night); the train left at 4 a. m. On reaching Boutte Station, I found Colonel Cahill stationed at that place with his regiment. He ordered me to leave one section of my battery with him, and to proceed myself with the other section to the La Fourche Crossing. I reached that place under about 10 a. m. of the 21st. My battery was soon unload and the pieces parked. I reported to Lieutenant-Colonel Stickney. He ordered out one of my pieces to shell a sugar-house, which I did most successfully, the distance being only about 1,700 yards; the shells, however, from some cause, refused to explode. At 6.30 p. m. the scouts came in, announcing the rebels coming down in force. In about 10 minutes my section was ready to move. While giving my attention to something else for a few minutes, Lieutenant-Colonel Stickney ordered off one of my pieces to take position on the left, in the Bayou road, to commence firing canister before any enemy could be seen. The position which he assigned was given before I had the least knowledge of its whereabouts-it was only by the firing of the piece that I could discover its position. I immediately rode to it, and found it stationed in the above road, about 2 rods in advance of our line of battle, in a most exposed position, and without any adequate support, and the piece was firing canister without stint. By this time, however, the enemy had formed in line of battle, and were rapidly advancing. The rebels now opened on us with howitzer, with shell and solid shot, but at too great a distance to seriously affect us any further than to frighten our infantry. The other piece into position to the rear of our front, and to the right of our right flank, and opened on the enemy's piece with fuse shell at 1,600 yards, very fortunately getting the range of the piece the first fire. The enemy's gun was silenced with the third shell. At this time the rebels were charging on our lines and were making a strong effort to turn our right flank. My piece being in position to enfilade their lines of attack on our flank, I ordered my piece to open on them with canister. The first fire was most disastrous and deadly on their ranks. Among the number who fell at our first discharge of canister was a the rebels fell back to the front, and finally made a hasty retreat, a large majority creeping off from the field on their hands and knees, so destructive was our fire. As soon as we had firing, I learned that, on the last charge of the rebels, the support of my left piece had fled, and that my sergeant gave the order to limber to the rear, when the horses became unmanageable, and ran away and left the piece. The sergeant was evidently frightened badly-that piece, if properly managed, could have been made the most effective piece in the field. The Bayou road was scarcely 14 feet wide, with a levee 10 feet high on the left, and a ditch on the right, grown up with a thick growth of bushes on either side. The piece controlled the road. After clearing the road of the enemy, the piece could have been turned so as to have raked the whole assaulting line of the enemy on our front. The sergeant allowed that golden opportunity to slip, and left his piece in the road. The moment the fact came to my knowledge, in order to mortify the sergeant of that pieces, I sent my sergeant with his limber and brought it off. The men at my piece behaved most gallantly-so much so, I have mentioned them in my report to Colonel Cahill. General, you may recollect, when last up to Apollo stables, that I had a deserter in confinement awaiting trial, and that on my desiring to withdraw the charges and try him again, your ordered him brought out and talked to him. General Emory shortly afterward ordered his release. He acted as Numbers 5 at the piece under my charge, and fully redeemed himself. The action lasted an hour and a quarter. For some reason or other, the enemy was not pursued by our cavalry. We had a company of cavalry of about 80 in number. We lost, I believe, 9 killed and 30 wounded; the enemy lost about 70 killed and over 200 wounded. The force on our side engaged did not exceed 400, but that of the rebels exceed 800. At 12 p. m. that night I saw Colonel Stickney, and advised him to retreat to Boutte Station, as the rebels had within 5 miles not less than 2,000 effective men, and, without any reenforcements, he must evidently overcome us. I forgot to mention that we had one 18-pounder brass piece, called the Saont Mary's gun, two 12-pounder howitzers, and one 6-pounder brass piece, all in position, which were well managed during that fight. The next forenoon was occupied with a flag of truce, which the enemy sent up asking the privilege of burying his dead. While this was pending, Colonel Cahill arrived with his forces. We were then about 1,100 strong, and, through the strength of our position, we could effectually defend our position again 2,000 rebels. The arrival of Colonel Cahill was distinctly seen by the rebels, and that night they commenced to retreat. On the next morning we made a forced reconnaissance to Thibodeaux, and found that all the rebels had left the country. On Monday afternoon, the 22d, the Fifteenth Maine regiment arrived, making us at least 1,700 strong. On this reconnaissance was this regiment, with 140 men of the One hundred and seventysixth New York, and my battery. Finding no enemy, all returned but the One hundred and seventy-sixth New York, who were left in possession of the town. With the forces which we had, we could successfully resist an attacking force of the enemy of 3,000. On the 24th, in the afternoon, negroes and white men came flying into camp, reporting that the rebels were advancing 3,000 strong, with eleven pieces of artillery, and that they were within 5 miles of Thibodeaux. The next report that came was that the rebs, finding that the One hundred and seventy-sixth New York, with a section of my battery, were holding the bridge at Thibodeaux, had changed their course, and were advancing on the other side of the Bayou La Fourche. At this juncture I received orders to take my caissons off the field and to load them up. Not knowing whether this meant an advance or a retreat, I went to one of the colonel's aides, and told him that it was necessary for me to know, in order to determine what to take with me. I was told to take with me. I was told to take everything. Colonel Cahill had telegraphed for cars, and they were hourly expected, and should have been all at the depot at 6 p. m. Matters began to look ominous. There was one locomotive here, but the colonel sent that off a distant of abut 5 miles with a company of the Twenty-third Connecticut to guard the railroad track; that, with the other trains failing to arrive, created a perfect panic. At 8 p. m. no trains arrived. The telegraph is in full operation. Major Morgan, of the One hundred and seventysixth New York, is ordered to burn the Thibodeaux Bridge, and to retreat to La Fourche Crossing. General Emory orders that if we do not have time to get everything off, to destroy rather than leave it. I had crossed my caissons, forge, and battery wagons, and about 15 of my horses. Colonel Cahill ordered all of my horses that were not leaded up, to retreat to Raceland Station, via the Bayou road. The panic increased; the colonel was anxious for my battery. I told him I could manage that well enough, because, if we were too hard pressed, I could retreat to Raceland Station. He ordered me to retreat at once. I ordered out of the field my two pieces, my own horses being loaded ink the cars. I occupied a seat on one of the libre chests, and proceeded with the pieces to the station, where I arrived about two hours before Colonel Cahill, who, it seems, had set out on foot at the time I left, leaving his aides to manage the retreat. Up to this time not a should of our own forces had seen or heard of an enemy. On our arrival at the station, I found that all the trains had gone forward to La Fourche Crossing, which, by the railroad, is 9 1/2 miles distant and 12 by the Bayou road. At 7 a. m. of the 25th, the trains began to arrive with the soldiers, stores, and baggage from the Crossing. At the time I left, the railroad bridge had been fired and had just commenced to burn. Up to the time the trains left, no enemy had been seen. What I deplore more than all else is the destruction of the brass pieces; the 18-pounder and the 12-pounder howitzers were spiked and thrown into the bayou, and the 6-pounder had its trunnions knocked off, and was spiked and its carriage burned. At about 10 p. m. of the 24th, the colonel's aides seemed to be possessed with the besom of destruction. My horses that were in the cars were turned out loose, and my harness and saddles were thrown promiscuously on the platform, and every infantry officer was making a grab for a saddle and a horse. I had, fortunately, left force enough to look after my property, who made a timely discovery enough to take care of it before it was lost. My private horses had been appropriated, and it was with difficulty that my sergeant could make the possessors give them up. The horses were gathered up, harnessed and saddled, and sent by the Bayou road to the station. Before Major Morgan fell back from Thibodeaux, Lieutenant Southworth sent up to the depot one of his pieces and his two caissons; as soon as they arrived, the colonel's aides ordered all the ammunition in the chests to be thrown into the bayou, amounting to 350 rounds, and personally carried out the order, and then ordered the pieces, with the two caissons in that condition, to proceed by the Bayou road to the station, without a round of ammunition to defend itself. My battery was ordered to this place, where I have been ever since; my horses stand hitched to their pieces; the men sleep by them every night. I inclose you a rough draught of the field of action* I find that it is quiet a detriment to have fine battery horses. I have to exercise the utmost vigilance to keep them from being stolen. The whole bridge seem to be of the opinion that I can furnish all of the officers with saddlehorses and saddles. I am even ordered to furnish adjutants and officers of the day with horses to ride. It has become a source of annoyance to me; perhaps it is all right. If I venture my own views, general, with reference to our "retreat," I trust you will not consider it amiss or an act of insubordination, as I should express it to no one else. In the first place, there was no necessity of a retreat, because we were strong enough to hold our position. In the second place, if the reports were true with respect to the advance of the enemy, my battery should have been retained until the last, as a matter of safety. The situation of the depot was such that my battery could have defended it against all the force that the rebels could bring to bear against it, and all the guns and stores could have been loaded up and sent off; when my battery, and the cavalry as an escort, could have retreated on the Bayou road to the station. Two thousand men, with one battery, can march back to La Fourche Crossing and never fight a battle, and, with the aid of a good gunboat, retake Brashear City. I am satisfied that the enemy are not 2,000 strong. I have not written this in a spirit of criticism, for I do not feel that I am competent to do that. But, general, you will always find the Twenty-fifth Battery prompt to do its duty, and ever rendering a good account of itself, while I am in command.

I am, general, your most obedient servant, |

|

|

|

|

|

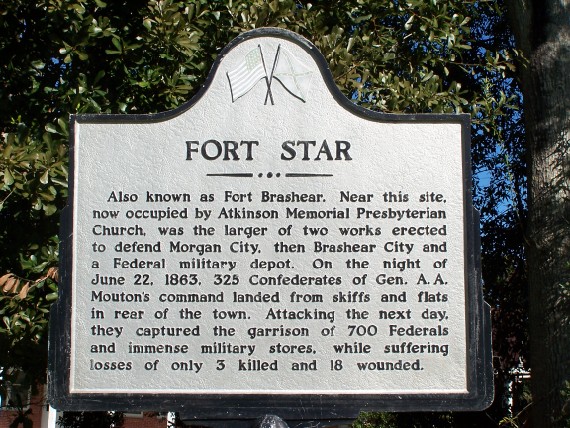

13) June 23, 1863 - Battle of Battle of Brashear City (current day Morgan City) - (Fort Star)

(Morgan City, LA)

|

Official Records on the Battle of Brashear City from U.S. War Dept. - The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Page(s) 223 - 224 W. FLA., S. ALA., S. MISS., LA., TEX., N. MEX. Chapter XXXVIII. OPERATIONS IN LA., WEST OF THE MISSISSIPPI. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Author: United States. War Dept.

Numbers 14. Report of Major Sherod Hunter, Baylor's (Texas) Cavalry, commanding Mosquito Fleet, of the capture of Brashear City. GENERAL: I have the honor to report to you the result of the expedition placed under my command by your order June 20. In obedience to your order, I embarked my command, 325 strong, on the evening of June 22, at the mouth of Bayou Teche, in forty-eight skiffs and flats, collected for that purpose. Proceeding up the Atchafalaya into Grand Lake, I halted, and muffled oars and again struck, and, after a steady pull of about eight hours, reached the shore in the rear of Brashear City. Here, owing to the swampy nature of the country, we were delayed some time in finding a landing place; but at length succeeded, and about sunrise commenced to disembark my troops, the men wading out in water from 2 to 3 feet deep to the shore, shoving their boats into deep water as they left them. Thus cutting off all means of retreat, we could only fight and win. We were again delayed here a short time in finding a road, but succeeded at length in finding a trail that led us by a circuitous route through a palmetto swamp, some 2 miles across, through which I could only move in single file. About 5.30 we reached open ground in the rear of and in full view of Brashear City, about 800 yards distant. I here halted the command, and, after resting a few minutes, again moved on, under cover of a skirt of timber, until within 400 yards of the enemy's position, where I formed my men in order of battle. Finding myself discovered by the enemy, I determined to charge at once, and, dividing my command into two columns, ordered the left (composed of Captains [J. P.] Clough, of [Thomas] Green's regiment [Fifth Texas Cavalry]; [W. A.] McDade, of Waller's battalion; [J. T.] Hamilton, of [L. C.] Rountree's battalion, and [J. D.] Blair, of Second Louisiana Cavalry) to charge the fort and camp below and to the left of th depot, and the right (composed of Captains [James H.] Price, [D. C.] Carrington, and [R. P.] Boyce, all of [G. W.] Baylor's Texas cavalry) to charge the fort and the sugar-house above and on the right of the depot; both columns to concentrate at the railroad buildings, at which point the enemy were posted in force and under good cover, each column having nearly the same distance to move, and would arrive simultaneously at the point of concentration. Everything being in readiness, the command was given, and the troops moved on with a yell. Being in full view, we were subjected to a heavy fire from the forts above and below, the gun at the sugar-house, and gunboats below town, but, owing to the rapidity of our movements, it had but little effect. The forts made but a feeble resistance, and each column pressed on to the point of concentration, carrying everything before them. At the depot the fighting was severe, but of short duration, the enemy surrendering the town. My loss is 3 killed and 18 wounded; that of the enemy, 46 killed, 40 wounded, and about 1,300 prisoners. We have captured eleven 24 and 32 pounder siege guns; 2,500 stand of small-arms (Enfield and Burnside rifles), and immense quantities of quartermaster's commissary, and ordnance stores, some 2,000 negroes, and between 200 and 300 wagons and tents. I cannot speak too highly of the gallantry and good conduct of the officers and men under my command. All did their whole duty, and deserve alike equal credit from our country for our glorious and signal victory.

I am, sir, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

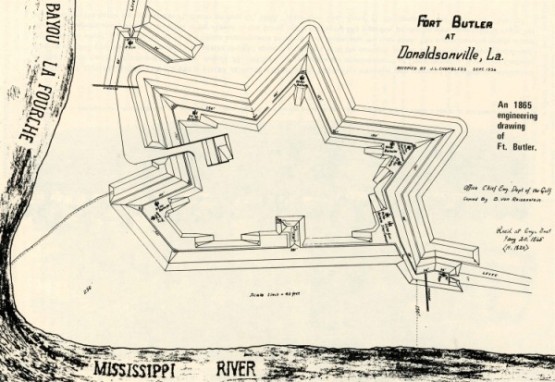

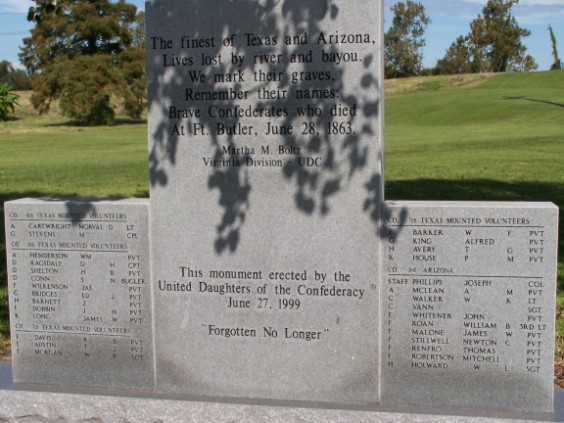

14) June 28, 1863 - Battle of Donaldsonville (Fort Butler) (Donaldsonville, Bayou Lafourche, LA)

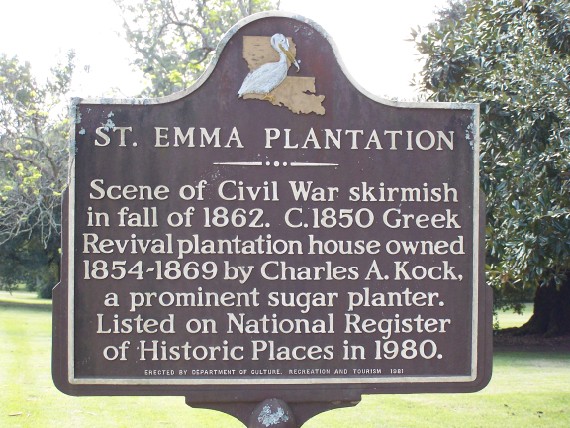

15) July 12-13, 1863 - Skirmish at Kock's Plantation / Cox's Plantation (Donaldsonville, Bayou Lafourche, LA)

16) May 16, 1864 -

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

sources:

U.S. War Department

War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies

130 vols.; Washington, D.C., 1880-1901

U.S. Navy Department

War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies

30 vols.; Washington, D.C., 1894-1922

Copyright © 2010 - All Rights Reserved - Louisiane Acadien / Acadian Melancon

Template by OS Templates